In this in-depth article, Pratik Gulati walks us through the many stages involved in creating an animated movie from scratch, whether it be the next Hollywood blockbuster or the shortest of short films. So if you're thinking about trying it yourself and want to know how it's done, or even if you're just curious about the process, this article is one you don't want to miss.

The production pipeline of a typical animated short or a movie can be divided into three stages : pre-production, production and post-production. In this article we will be discussing these three key stages in detail.

Pre-Production

The first process in the animation pipeline, and also one of the most important, is pre-production. It begins with the main concepts which are initially turned into a full story, and then, once the story has been finalized, other things such as the script, shot sequence and camera angles are worked on.

Some major components of pre production are Story Boarding, Layouts, Model Sheets and Animatics.

...they also provide a visual reminder of the original plan; something that can be referred back to throughout the production.

Story Boarding

The Storyboard helps to finalize the development of the storyline, and is an essential stage of the animation process. It is made up of drawings in the form of a comic strip, and is used to both help visualise the animation and to communicate ideas clearly. It details the scene and changes in the animation, often accompanied by text notes describing things occurring within the scene itself, such as camera movements.

Not only can storyboards be especially useful when working in group environments (something quite common in the animation industry,) but they also provide a visual reminder of the original plan; something that can be referred back to throughout the production.

Layouts

Once the storyboards have been approved, they are sent to the layout department which then works closely with the director to design the locations and costumes. With this done they begin to stage the scenes, showing the various characters' positions throughout the course of each shot.

Model Sheets

Model sheets are precisely drawn groups of pictures that show all of the possible expressions that a character can make, and all of the many different poses that they could adopt. These sheets are created in order to both accurately maintain character detail and to keep the designs of the characters uniform whilst different animators are working on them across several shots.

During this stage the character designs are finalized so that when production starts their blueprints can be sent to the modeling department who are responsible for creating the final character models.

Animatics

In order to give a better idea of the motion and timing of complex animation sequences and VFX-heavy scenes, the pre-visualization department within the VFX studio creates simplified mock-ups called “Animatics” shortly after the storyboarding process.

These help the Director plan how they will go about staging the above sequences, as well as how visual effects will be integrated into the final shot.

Production

Now that the storyboard has been approved the project enters the production phase. It's here that the actual work can start, based on the guidelines established during preproduction. Some major parts are layout, modeling, texturing, lighting, rigging and animation.

[layout artists] produce the 3D version of what storyboard artists had previously drawn on paper.

Layout

Using lo-res models or blocks of geometry in the place of the final set and characters, the Layout Artist is responsible for composing the shot and delivering rough animation to the animators as a guide. What they produce is the 3D version of what the storyboard artists had previously drawn on paper.

During this stage the Director approves camera moves, depth of field and the composition of the models making up the set and set dressing. It is then the responsibility of the Modeling department to deliver these approved set, prop and character models in the final layout stages.

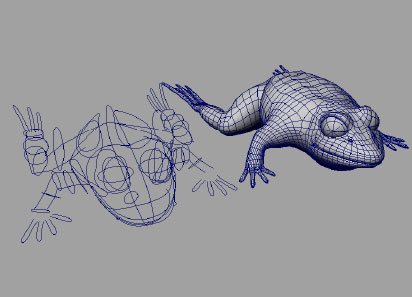

Modelling

Modelers are usually split into two or more departments. Whilst organic modelers tend to have a sculpture background and specialise in building the characters and other freeform surfaces, hard-surface modelers often have a more industrial design or architectural background, and as such they model the vehicles, weapons, props and buildings.

Working closely with the Art Directors, Visual Effects Supervisors and Animation Supervisors, modelers turn the 2D concept art and traditionally sculpted maquettes into high detail, topologically sound 3D models. They then assist the Technical Animator and Enveloper as the model has a skeleton put in place and the skin is developed. Following this, the model may be handed back to the Modeler, who will proceed to sculpt facial expressions and any specific muscle tension/jiggle shapes that may be required.

Once the model is approved, it will be made available to the rigging and texture paint departments, who complete the final stages in preparing the model for animation and rendering. With luck, the model will move through the production pipeline without coming back for modeling fixes, although some amount of fixes are inevitable - problems with models sometimes don't appear until the rendering stage, in which case the lighter will send the model back to be fixed.

Texturing

Whether creating a texture from scratch or through editing an existing image, Texturing Artists are responsible for writing shaders and painting textures as per the scene requirements.

Working hand-in-hand with the surfacing and shading departments, textures are painted to match the approved concept art and designs which were delivered by the art department. These textures are created in the form of maps which are then assigned to the model.

...lighting TDs combine the latest version of the animation, the effects, the camera moves, the shaders and textures, and render out an updated version every day.

Lighting

Not only does a Lighting Artist have to think lighting the individual scenes, they also have to consider how to bring together all of the elements that have been created by the other departments. In most companies, lighting TDs combine the latest version of the animation, the effects, the camera moves, the shaders and textures into the final scenes, and render out an updated version every day.

Lighters have a broad range of responsibilities, including placing lights, defining light properties, defining how light interacts with different types of materials, the qualities and complexities of the realistic textures involved, how the position and intensity of lights affect mood and believability, as well as color theory and harmony. They are required to establish direct and reflected lighting and shadows for each assigned shot, ensuring that each shot fits within the continuity of a sequence, all the while aiming to fulfill the vision of the Directors, Production Designers, Art Directors and VFX Supervisors.

Rigging

Rigging is the process of adding bones to a character or defining the movement of a mechanical object, and it's central to the animation process. A character TD will make test animations showing how a creature or character appears when deformed into different poses, and based on the results corrective adjustments are often made.

The rigging department is also involved in developing cloth simulation – so as well as making a character able to clench their fist or rotate their arm, the rigging and cloth department is responsible for making their costume move in a believable manner.

...planning a character's performance frame by frame uses the same basic principles first developed for 2D animation.

Animation

In modern production companies, the practice of meticulously planning a character's performance frame by frame is applied in 3D graphics using the same basic principles and aesthetic judgments that were first developed for 2D and stop-motion animation. If motion capture is used at the studio to digitize the motion of real actors, then a great deal of an animator's time will also be spent cleaning up the motion captured performance and completing the portions of the motion (such as the eyes and hands) that may not have been digitized during the process.

The effects team also produce elements such as smoke, dust, water and explosions, although development on these aspects does not start until the final animation/lighting has been approved as they are integral to the final shot and often computationally heavy.

Post-Production

Post-production is the third and final step in film creation, and it refers to the tasks that must be completed or executed after the filming or shooting ends. These include the editing of raw footage to cut scenes together, inserting transitional effects, working with voice and sound actors and dubbing to name just a few of the many post-production tasks.

Overall, however, the three main phases of post-production are compositing, sound editing and video editing.

Compositing

The compositing department brings together all of the 3D elements produced by the previous departments in the pipeline, to create the final rendered image ready for film! Compositors take rendered images from lighters and sometimes also start with compositing scripts that TDs develope in order to initially comp together their dailies (working versions of the shot.)

General compositing tasks include rendering the different passes delivered by a lighting department to form the final shot, paint fixes and rotoscoping (although compositors sometimes rely on mattes created by a dedicated rotoscoping department), as well as the compositing of fx elements and general color grading.

Sound Editing

This department is responsible for selecting and assembling the sound recordings in preparation for the final sound mix, ensuring lip sync and adding all of the sound effects required for the final film.

Video Editing

Video editing is the process of manipulating and rearranging shots to create a seamless final product, and it is at this stage that any unwanted footage and scenes are removed. Editing is a crucial step in making sure the video flows in a way which achieves the initial goal. Other tasks include titling and adding any effects to the final video and text.

Conclusion

The production pipeline detailed above is broadly common in most studios, however each studio is likely to have a custom pipeline determined by the type of project they are currently undertaking. A 2D production pipeline starts with workbook and goes all the way through final checking, composting and film output, whilst the 3D CGI production process emphasizes the design, modeling and rigging and animation stages. Moreover, animation production is a very coordinated process where different teams of artists work together while utilizing optimum resources and achieving the initial goal in the time available.